Vikas Swarup, Six Suspects (London: Black Swan 2008). The crime novel as vehicle for a darkly humorous and highly critical portrait of modern India.

Opening sentence: Not all deaths are equal. There’s a caste system even in murder.

For the first time this blog travels to India, as part of a concerted effort to broaden its transnational criminal horizons.

Six Suspects is the second literary offering of Vikas Swarup, who hit the international jackpot when his highly-praised first novel, Q&A, was adapted for film as the phenomenally successful Slumdog Millionaire (eight Oscars and numerous other accolades). Not bad for a book that was written in a mere two months.

Six Suspects is a rather unusual crime novel. While drawing heavily on the conventions of classic detective fiction (there’s a murder, a drawing room of sorts, and the eponymous set of suspects), Swarup uses the genre primarily for satirical purposes, providing the reader with a darkly humorous and often scathing critique of modern India.

The suspects – a bureaucrat, a Bollywood actress, a thief, a politician, an American tourist and a tribesman from the Andaman Islands – are selected for the spectrum of perspectives they offer on contemporary Indian society, and allow Swarup to explore his key themes of political corruption, power and class in an uncompromising fashion (pretty daring given his day job as a member of the Indian civil service; currently Consul-General of India in Osaka-Kobe, Japan).

Much of the novel is taken up with tracing the life stories of the suspects and the motives that they might have had for killing Vivek ‘Vicky’ Rai, a disreputable thirty-two-year-old businessman and playboy, who also happens to be the son of the powerful Home Minister of Uttar Pradesh. In contrast, relatively little emphasis is placed upon the process of investigation: the role of detective is played in part by Arun Advani, a journalist renowned for exposing corruption and injustice, but he only features significantly at the beginning and the end of this chunky 557-page text.

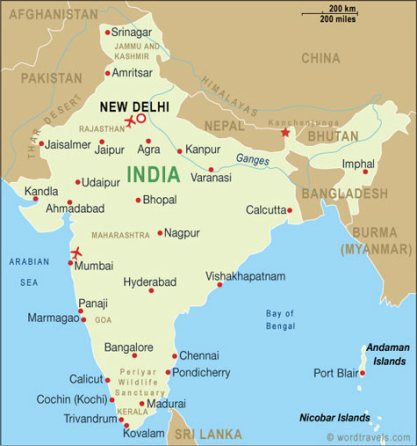

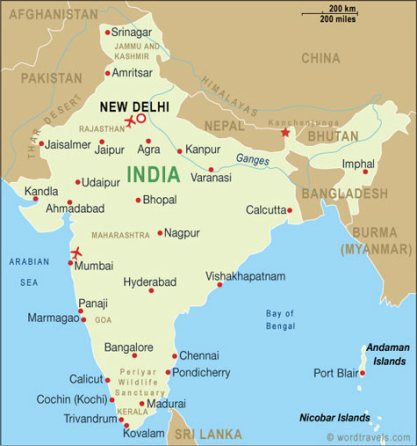

I found Six Suspects very enjoyable in a number of respects. As someone who has visited India in the past, the novel’s evocative descriptions of the sights and sounds of everyday life, and the huge disjunction between rich and poor rang very true. The novel also travels widely around India, beginning and ending in Delhi, but taking in other locations such as Srinagar, Jaisalmer, Varanasi, Kolkata and the Andaman Islands on the way (the latter are a remote and very beautiful group of islands in the Bay of Bengal that ‘belong’ politically to India, and which are home to ethnic tribes such as the Onges and Jarawa). The novel thus takes readers on a wide-ranging geographical and cultural journey which will be highly rewarding for those with an interest in India.

Another hugely enjoyable aspect of the novel is its biting satirical humour, and its witty nod to Salman Rushdie and magical realism (I particularly liked the possession of a grumpy, philandering ex-politician by the spirit of Mahatma Gandhi).

On the minus side, I felt the novel was a bit overlong and that its depiction of some characters and incidents was too exaggerated to be effective in the larger context of Swarup’s satire. As a result, the narrative felt rather uneven at times, and while I remained admiring of the author’s ambitious use of the crime genre to create a satirical portrait of India, I wasn’t sure that he’d completely succeeded in his aim when I closed the book for the final time.

I discovered Six Suspects at our city library, which has a superlative collection of crime fiction. If you’d like to read an extract from the novel, you can do so here on the author’s website.