Given the international focus of this blog, it’s not often that I watch home-grown British crime drama. But having caught the first episode of BBC One’s Happy Valley, I’ve been completely gripped, and tonight’s hotly anticipated finale did not disappoint. This hard-hitting six-part series, which traces the fall-out from a kidnapping in the West Yorkshire valleys, is superbly written (by Sally Wainwright) and directed (by Wainwright, Euros Lyn and Tim Fywell). Lead actress Sarah Lancashire gives an *absolutely outstanding* performance as policewoman Catherine Cawood, with an excellent supporting cast.

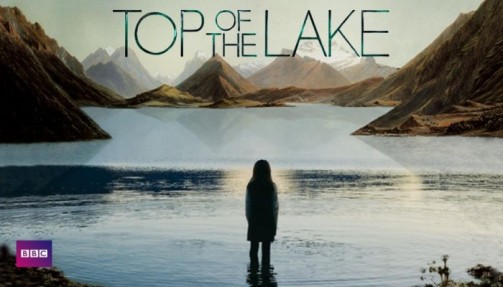

I’m prepared to say that this is the best crime drama I’ve seen all year, with perhaps one exception … the New Zealand crime drama Top of the Lake, which I watched on DVD in March (aired on BBC Two in 2013). It’s equally well written (by Jane Campion of The Piano and Gerald Lee) and directed (by Campion and Garth Davies), with Elisabeth Moss of Mad Men in the lead role of Detective Robin Griffin. This time, the investigative focus is on the disappearance of a twelve-year-old schoolgirl, Tui Mitcham.

Aside from their quality, the dramas have a striking number of things in common:

- Both feature wonderfully strong female investigators, who have each experienced the impact of crime in their own lives. These past traumas – and their identities as women and mothers – shape their responses to the crimes that they witness in the present.

- There is a focus on gender and power, with both dramas showing women having to negotiate and survive extreme male violence. (There’s been media debate about whether Happy Valley is too violent, but in my view, it effectively illustrates the reality of certain types of crimes and isn’t gratuitous). In each case, older women step in to protect younger women when they can.

- Both dramas are set in socially deprived areas, where criminality has become a way of life for many. But they also point a finger at the supposedly respectable middle classes, who are not as morally upstanding as they pretend to be (there’s a nice touch of Fargo in Happy Valley).

- Each makes excellent use of landscape – the importance of which is indicated by the series’ titles. Top of the Lake uses haunting images of New Zealand’s South Island to suggest the isolation of its central characters. Happy Valley’s ironic title and the rolling Yorkshire countryside are used to highlight the disparity between the physical beauty of the setting and the violence within it. (Thanks are due to Elena, whose cracking post on True Detective and its use of landscapes got me thinking about this aspect of the dramas).

- And I know I’m repeating myself, but …. fantastic actresses in complex, nuanced, gritty, challenging, leading, female investigator roles. More, more, more of these women please!

Elisabeth Moss as Det. Robin Griffin.

If you haven’t yet had a chance to see these dramas, then you have a treat of the highest order before you. Enjoy!

Good news: it looks like there could be a second series of Happy Valley according to this Radio Times interview with Sally Wainwright. Warning: Lots of spoilers!

And here’s a review of the finale by Mark Lawson for The Guardian.